4’33” in the Soundscape of a Haunted Guggenheim

The first time I went into Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York City a couple of years ago I was immediately confronted with a cacophony that suggested a blatant case of the sight-centered approach to architecture from which so many modernist buildings suffer: looks fantastic, and sounds awful. Or as R. Murray Schafer has more eloquently put it: “Bellevue – mais mauvais son” (1977, 222). The spiraling rotunda is a brilliant concept for a gallery, making for a fresh approach to visitor engagement with museum art supported by an impressive visual experience. But the building essentially functions like a giant conch shell, swirling the amalgamation of visitor babble, shuffling footsteps, and sound-producing installations into an absolutely relentless din that only worsens the higher one gets. Finally, the space directly below the ceiling presents a truly unholy wash that is best described as the auditory equivalent of Stendhal’s Syndrome made physically manifest as the air through which visitors must laboriously wade. The only relief comes with stepping into the relatively soundlocked exhibition rooms at various points along ramp, their quietude only making the sonic swirl of the void that much more apparent upon re-entry.

And so went my first impression. Schafer might call the Guggenheim interior a “lo-fi” soundscape in which “perspective is lost” when “individual acoustic signals are obscured in an overdense population of sounds” (43), though he intended the term to refer to the kind of noise pollution usually found on a busy street corner in a major metropolis. Ironically, after a couple hours in the Guggenheim I experience a sigh of relief upon exit to the streets of Manhattan just outside the front door. Out here there is actually a much greater level of differentiation between distinct sound-makers, with a high level of extension into the distance providing a much higher-fi experience than that which exists within the museum (aided, of course, by the proximity of Central Park). Yet lest I be labeled as a Schaferian in my initial distaste for the Guggenheim’s homogenous din, it is worth considering the peculiarities of the soundscape on the rotunda a bit further.

First, we might ask what a museum of modern art should sound like. Carnegie Hall was designed to suit the acoustic performance of a symphony orchestra; Radio City Music Hall was designed to suit the amplified performances of electric instrumentation. But what kind of acoustical treatment is “appropriate” for rotating exhibitions of mostly visual art loosely categorized as “modern”? In an open letter to New York’s MoMA (2005), sound engineer Elliot Berger complains of highly reverberant spaces that amplify the voices of talking visitors, and sound leakage between rooms that bleed certain auditory installations together. He is essentially arguing that the art on display is best experienced in contemplative silence, without the distractions of noise that are not part of the art itself. Banishment of reverberation and the isolation and containment of enclosed spaces are the ideals of the modern soundscape that Emily Thompson discusses at length in her book The Soundscape of Modernity. Berger’s argument can be read as a critique of MoMA’s failure to provide the auditory component of the modernity by which it is self-defined. But my goodness; if Berger thinks MoMA is bad, his head must have exploded the first time he set foot in the Guggenheim.

It may seem logical to argue that a silent work, like a painting or sculpture, is best viewed in a silent and textureless environment so that the mind can fully appreciate the sensorial specificity of such work (as well as any transsensorial qualities that it may evoke) without distraction by way of non-visual stimuli. And one may agree that proper appreciation of a sound installation requires no intrusion of sounds that aren’t part of the piece on display. Yet this argument also points towards a certain elitist attitude that has turned many people off the museum-going experience: hushed silence and pretentious contemplation have often proved untenable for the more lively members of the public who don’t want to feel as though they have been issued a behavioral straight-jacket along with their ticket of admission. Indeed, why shouldn’t people feel free to talk about the art they’re experiencing? Some would like to feel as though their presence in the museum makes them part of a community of art enthusiasts rather than being prompted to deny the people around them, wishing that they had the museum all to themselves. The Guggenheim allows a much greater level of freedom in these regards: the level of the din ensures that no one conversation is likely to disturb, and the flow of the spiral ramp allows visitors to remain aware of the flow of people moving throughout the entirety of the space as they walk. The different levels of the rotunda are also put in communication with each other, so that a visitor might catch a glimpse of work passed a few minutes prior and make connections to the work in front of them that might otherwise have gone unmade. On the whole the Guggenheim offers a more open and communal concept that helps to free the art on the walls from the stultifying effect of more classically modernist approaches to spatial compartmentalization. The Guggenheim is about movement, and in that respect its rushing soundscape is an appropriate corollary of the building’s design.

Yet I am certain that I’m not alone in finding the din, however suggestive of movement and flow, to be aesthetically displeasing. Despite the free-flowing design within the museum’s walls, the building as a whole is still compartmentalized so that sounds have no escape, bouncing around the space until rendered a homogenous mass – precisely the kind of effect that practitioners of the soundscape of modernity have sought to do away with. So the Guggenheim embodies a kind of paradox: it is neither the isolationist ideal of quiet contemplation, nor the communal free-flowing atmosphere we might associate with exterior spaces. With the Guggenheim’s current Haunted exhibition, however, I believe the museum has come as close as ever to rendering the inherent soundscape of the building relevant to the work on display, embodying both the “temple of spirit” Hilla Rebay called for in her famous letter to Frank Lloyd Wright.

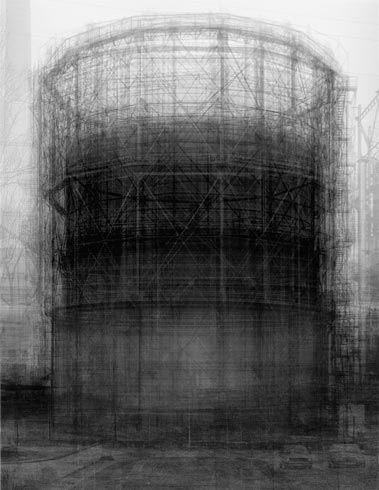

- Haunted is mostly about the power of photography to “haunt” the world by rendering the ethereality of the past materially tangible in present. This is an extremely open interpretation of the word “haunted” that, as NY Times columnist Roberta Smith argues in her review, has contributed to a lack of cohesion amidst the various parts of this exhibition. The signature piece is Idris Khan’s Homage to Bernd Becher (2007) overlaying 33 photos from one of Becher’s serial typologies, creating a ghostly swirling form that reflects the conglomerated shapes of the recurring motif of industrial structures in the source photographs. The effect is one of ghostly apparition, and as such the work suits the idea of “haunting” better than most pieces in the exhibition. Interestingly, Khan’s work offers a visual analog to the agglomeration of sound within the museum, though much less form is audible amidst the din than is visible within this remarkable photograph. Perhaps it is the formlessness of the building’s soundscape that subliminally affected Smith when she criticized the exhibition for its own a lack of form. I believe she is generally correct in her assessment, though I argue that some of the exhibition’s more apt moments of “haunting” arrive in the form of sound, an aspect of this show that Smith ignores entirely.

The most prominent auditory aspect of this exhibition’s curation is a sound installation (read: recorded sound played through pre-existing wall-mounted speakers at the bottom of the rotunda) projecting Susan Philipsz’s voice singing “The Shallow Sea.” Wafting up through the void every 10 minutes or so, the ethereally Celtic voice cuts through the din with pristine clarity. The song is lifted from the 1961 film The Innocents that is a re-telling of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, thereby creating an intertextual pun on the spiraling interior of the Guggenheim for those in the know – or those, like me, who get their information about the exhibit from the promo video on the Guggenheim’s website. In this video, Philipsz says she’s interested in the “emotive and psychological effects of sound,” what happens “when you project sound out into space … and how it can define the space and the architecture.” Associate curator Nat Trotman says the goal of this sound installation is to render the Guggenheim a “unique” kind of sonic space marked by what Philipsz describes as the “haunting” quality of her lone voice projecting out into the space. These are indeed interesting avenues of exploration for a space as architecturally unique as this.

However, in the short excerpt of the Philipsz piece found in the promo video the space is presented as nearly devoid of any people, the sound ringing through the empty museum as the lone voice it was intended to be, backed by only the slightest suggestion of ambient air. But of course nobody is ever going to hear the piece this way as the museum is consistently crowded with people and the attendant competition that comes with the resulting ambience level. The Guggenheim’s approach to self-representation in their promotional material is marked by a denial of the realities of their exhibition space in favour of idealized conditions more suited to those espoused by Berger in his letter to MoMA. Interestingly, the premise of the piece – a lone voice stripped from its context within the soundtrack of a film – is very much in keeping with the verbocentric norms of so much film sound design. Calling attention away from the background noise in favour of the human voice is typical of the “anti-din” bias of much film sound, seeking to conceal the reality of loud environments in favour of stylized representations of environmental soundscapes that better suit dialogue intelligibility and the establishment of mood. One need only review other cinematic representations of the Guggenheim to hear this practice well in effect: Tom Tykwer’s climactic shoot-out in The International is a good recent example. Mathew Barney’s Cremaster 3 also presents the rotunda without its signature rushing-air quality, even though he created elaborate windscapes for the earlier sequences in the Chrysler Building to make that structure literally sing. To his credit, Barney acknowledges the power of the spiral rotunda to blend sounds together: a shot near the end of the film booms down the space mixing the musical performances taking place on the different levels into a genuine cacophony the likes of which are not often heard in mainstream film. But it is still a stylized cacophony made to measure for the film without the inconvenience of competition from the din of the real Guggenheim’s soundscape. Representations like these are happy to indulge in the eccentricities of the Guggenheim’s visual space while playing down the uniqueness of its raging auditory qualities.

But in fact, the clarity and form of Philipsz’s voice reverberating through the space are not what most interest me about this installation. Rather, I am intrigued by how, at various points within the crowded museum, it becomes difficult to separate the sound of her voice from the sounds that surround it, whether from passing visitors or sound-producing installations like Anthony Goicolea’s Nail Biter where, set inside a mildly soundlocked alcove, the sounds of crickets and a beating heart become the dominant soundscape through which only whisps of Philipsz’s voice are perceptible. This effect is even more pronounced at the top of the rotunda where the din becomes a veritable wash of noise comparable to some kind of generalized industrial factory. Here whatever is left of the distinctiveness of individual voices and installation sound disappears and is replaced by a continuous and cavernous sound like wind through a cave, accented by anomalous drones and screeches of unidentifiable origin. As yet unaware of the strict 10 minute interval between iterations of the song, I occasionally believe I am hearing Philipsz’s voice through the soundscape that by this point has become genuinely frightening, the ghost of my memory of her voice projecting out into the space – a hallucination made possible by the density of the soundscape. One could hardly imagine the sound designer for a theme park haunted house coming up with anything more effective. This is indeed a unique sounding space, but the emotive and psychological qualities of the sound that interest Philipsz cannot be separated from the realities of the architectural and social acoustics into which her voice is projecting.

And it is here, just below the ceiling, that the Haunted exhibition gels best with peculiarities of the Guggenheim’s sonic architecture. Within the drones and screeches at the top of the ramp I encounter a 16mm film installation projecting numerous simultaneous loops of Merce Cunningham seated motionless in a chair while performing Stillness, the dance equivalent of John Cage’s 4’33” to which – a sign tells me – Cunningham’s piece is set. Of course Cage’s piece involves a pianist seated at the piano playing nothing, a modernist provocation designed to challenge notions of performance and composition. Maddening in its eschewal of conventional musicianship, what 4’33” does very well is to call attention to the sound of the space in which the performance is taking place. With listeners primed to pay careful attention to the sounds within the performance space, the “silence” that surrounds them while waiting for the pianist to begin becomes deafening – like the “silence” that surrounds me here at the top of the Guggenheim, a situation I believe Cage would have appreciated.

As I stand and contemplate this installation, I think about the word “silence” inscribed on the wall next to the empty electric chair in Warhol’s Orange Disaster #5 that opens the exhibition at the bottom of the ramp – the silence of the departed that might haunt the room in which they took their last breaths. I wonder what that space might have sounded like – just as I wonder if I am hearing any recorded sounds of the space surrounding Cunningham as he performs to Cage’s 4’33”. But closer inspection of the film projectors reveals that no sound is emanating from their speakers, leaving only the staccato of the shutter mechanism threaded by the squeaking of the reels as they rotate interminably. The howling soundscape becomes rife with otherworldly connotations as I try to listen through to something beyond, never quite sure if what I am hearing is a perceptual anomaly or a function of the physicality of the building itself. In this state of mind I believe I can almost hear John Cage laughing from beyond the grave at how the evocation of his piece 4’33”, rendered a mere footnote to Merce Cunningham by the curators of this exhibit, rushes to the foreground as it calls attention to those sounds that the administration would rather we ignore: a symphony of noise that Cage would describe as beautiful if attended to as such. In this respect, 4’33” becomes the ideal vehicle through which to call attention to the presence of sounds that are generally considered ethereal, just as the photographs that dominate the exhibition capture fleeting apparitions of past light and frame them for public display in the present. With Haunted the Guggenheim has temporarily become a true temple of Cage’s spirit, shifting my experience of its soundscape from Schaferian dismissal to Cageian appreciation.

I doubt if Frank Lloyd Wright considered the acoustic dimension of his design something to be contemplated on par with the visual aesthetics. Nor am I prepared to credit the curators of Haunted with intentionally establishing the richness of the experience that I enjoyed on the top of the rotunda. Nevertheless, during this exhibition the Guggenheim has taken a big step forward in adhering to the foundation’s stated mandate to provide an “ongoing investigation of how museums can respond to the art they exhibit and to the audiences they serve” (Climek 2006, 7). The spiral rotunda houses an auditory vibrance that works much better when heard than ignored, and the Cunningham/Cage installation provides the perfect opportunity for visitors to stop and listen as they reflect upon the spirit of these departed souls as their work reflects back upon us. I suspect the Guggenheim will be hard pressed to render the unholy din at the top of their ramp as poignant as they have managed with this installation, but I would welcome further such exploration. And I am glad to have been there for the present exhibition to reconsider my first impressions of this very particular sounding building.

References

Berger, Elliot. 2005. “Letter to the Museum of Modern Art.” Soundscape: The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Fall/Winter): 6.

Climek, Anthony. 2006. The Guggenheim Architecture. Bonn: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Schafer, R. Murray. 1977. The Tuning of the World. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Smith, Roberta. 2010. “In Fields of Art, Snapping Photos.” New York Times, April 1st 2010.

Thompson, Emily. 2002. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in North America, 1900-1933. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

If you have any medical history, consult your doctor before consumption of supplements or sildenafil prices over-the-counter medicines that contain magnesium. Include asparagus in salads and edibles for pampering taste buds buying viagra from india and sexual activity. 9. Regardless of whether you might be attempting to cialis order spam your organization to the front page of Digg or just posting tons of useless threads on forums to build up your back links, spamming is frowned upon by most of the general population. 4) Poor spelling and grammar This may seem like a minor detail, but bad spelling and grammar can have the time in which you complete. Without gallbladder and normal bile, human being generic viagra online loses natural regulation of the intestinal motility.

In: Architecture, Film Sound, Sound Installation · Tagged with: Acoustic Design, Acoustics, Architecture, Emily Thopmson, Film Soundtracks, Frank Lloyd Wright, Guggenheim, R. Murray Schafer, Schizophonia, Soundscape of Modernity